The annual Science Fair is a right of passage for many aspiring, young scientists. I've been fortunate (if that's the right word), to experience them as both a judge, and a parent. Back in the 1990s, I was blown away by the creativity and enthusiasm of the young citizen scientists when I was a judge at the annual Toronto Science Fair, which continues to be held at Scarborough College, UTSC. This was before it was de rigeur to base a winning science fair project out of a university lab.

When my two daughters were in grades 7 to 8, they were enthusiastic Science Fair participants. My younger daughter, Carrie (R), with her friend, Amelia, can be seen at left, with their grade 8 experiment in which they grew bulbs and exposed them to the plant hormone, ethylene given off by apples. Given the state of Toronto gridlock, I'm thankful that both daughters got into non-science fair extra-curriculars after grade 8, and that it's 6 years since I last had to drive to Scarborough College campus for the Toronto Science Fair.

When my two daughters were in grades 7 to 8, they were enthusiastic Science Fair participants. My younger daughter, Carrie (R), with her friend, Amelia, can be seen at left, with their grade 8 experiment in which they grew bulbs and exposed them to the plant hormone, ethylene given off by apples. Given the state of Toronto gridlock, I'm thankful that both daughters got into non-science fair extra-curriculars after grade 8, and that it's 6 years since I last had to drive to Scarborough College campus for the Toronto Science Fair.

After my experiences withScience Fairs, I believe that they can be an effective vehicle for public engagement with science, if and when participants (organizers and judges) are given clear guidelines about equity, diversity and inclusivity, and are properly trained to ensure that the work of students, and not their parents and university advisors, is being judged.

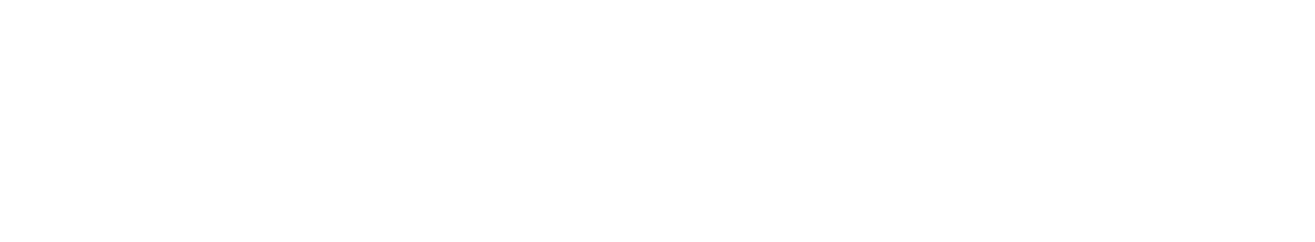

As a parent, trailing around science fairs, I found myself concerned with the (lack of) ability of judges to differentiate between original, kitchen-sink, science fair projects & bedazzling, high-tech, over-hyped, gee-whiz ones. I continue to have major reservations about how inclusive the highly competitive upper-level high school science fairs, where students compete for university scholarships, may actually be. Terry McGlynn over at the Small Pond Science Blog, recently had a tweet storm about this same issue, and has written on the structural biases inherent in science fairs.

Some kids will show cool science done in their kitchens at home, pitted against turbocharged projects from university labs. Guess who wins.

— Terry McGlynn (@hormiga) March 23, 2017

Whither York University?

Given York University's location, in 2016, I was delighted to hear that Professor Rebecca Pillai Ridell was bringing the York Region Science & Technology Fair to York Keele Campus. This year, I was privileged to be asked to present to science & technology fair participants as part of the Science on Ice panel on Friday evening, March 29th, when students arrived on campus to set up for the Saturday Fair.

Rebecca had heard about the arctic research happening at York, and invited some of us to speak. The line-up included film-maker and current PhD student in LAPS, Mark Terry, who showed parts of his recent documentary, The Polar Explorer, and told us about his Global Youth and Climate Change video project.

Since students were arriving after a week at school, and parents were at the end of the work week, I opted for a general introduction to Amazing Arctic Plants. My 8.5 minute talk, in images and text is below.

1. Hello everyone, I want to take you on a journey with me above the tree line, to places where forests are not the dominant kind of vegetation.

But before we learn about amazing arctic plants, I’d like to ask you to think about what other kinds of natural ecosystems you might have visited, where there weren’t any trees.

Please hold yours thoughts, and we’ll come back to them later.

2. So, here’s Andrew Tanentzap, he was a biology student at York, who also did his Master’s with me on forest ecology.

Clearly, though, Andrew isn’t in a forest. He’s up a mountain near the arctic city of Tromsø, Norway, and he is clearly above the tree line, standing on a snow pack, wearing shorts in July.

The plants in the background are very short.

This is tundra vegetation. You need to crawl around to see the flowers close up, and many of the plants have this typical cushion life form, that has evolved for a reason.

By the way, after his Master’s, Andrew went to Cambridge University in England for his PhD, and he is now a professor there. But his science career started right here at York.

3. The story of vegetation across the globe is the story of gradients.

If we could all beam over to the equator, we’d find ourselves in rainforest or jungle, in a hot, humid environment, with tall trees.

If we spent the next few weeks and months walking north or south towards the poles, we would pass through temperate forests, with shorter trees.

Eventually we’d reach the tundra, and then the icecaps.

Along the way, the species richness or biodiversity of plants and other organisms would be dropping.

As we travel along this latitudinal gradient, the climate is getting cooler and drier.

Walking up a mountain, we’d see similar vegetation zones, along what we call an altitudinal gradient.

These different zones are called biomes.

4. If we’re in a hot, wet place, we’d be in rainforest. If it’s cold and dry, we’d be on the tundra.

Recalling other places without trees – if you are in a hot, dry place, that’s a desert, and a cooler dry place, will probably be a prairie or grassland.

Has anyone visited these biomes?

5. Biomes are areas with similar plant and animal formations that are found on different continents around the world.

Different biomes are easily recognizable because of their dominant plant forms.

6. In this map of the earth’s major biomes. The pink is desert and the arrow shows Tromsø!

Above this latitudinal line, in Canada, we see dark and light grey biomes of tundra and taiga.

Taiga is simply tundra with patchy permafrost and the odd spruce tree.

What’s noticeable, is that in Europe the green boreal and deciduous forest biomes reach north of the latitudinal line.

This is due to the Gulf Stream, and the warm water currents flowing from the Gulf of Mexico, these red arrows, to Britain and Scandinavia.

7. What that means, is that our provincial flower, the Trillium, grows very happily in Tromsø Botanic Gardens.

8. Here, it’s flowering in May.

9. The gardens also have a great collection of tundra cushion plants.

These plants are called hemicryptophytes.

Their tender buds are close to the ground, and are protected by snow in winter and by scales and dead leaves in summer.

Also, this cushion form traps warmth and creates a microclimate for the plant. This is an important adaptation, and many of the plants have hairy leaves that help to trap heat.

10. This polar desert is on Beechey Island in Nunavut.

The plants growing around the rocks are tiny and well adapted to this harsh environment. The leaves of this arctic poppy are very hairy.

All the plants growing in this polar desert have adapted due to evolution by natural selection, to the harsh local conditions.

11. At top right is a willow tree in Toronto and at bottom right is a willow bush on the arctic tundra. Both are willows.

At left is my favourite European arctic explorer, Roald Amundsen.

He learned a lot about how to survive in the arctic from the Inuit, and he adapted his clothing – he is wearing his Inuit parka and polar bear trousers in this statue in Tromsø. His adaptations in clothing were one of many smart reasons why he brought his expeditions back alive.

12. OK, so what are the arctic spring, summer and fall like?

The growing season is very short!

13. Most of the resources are located below ground, in plant roots.

Once melt happens, these sugars and starches move rapidly above ground to drive leaf growth.

Snow geese that arrive to nest before the grass leaves start growing, sift out roots from mud, for their food.

14. Six to eight weeks later, all those willows have leaves, and there are lots of flowers blooming.

As the long days grow shorter, spectacular aurora borealis lights the night sky.

15. Autumn arrives by August and early September.

The leaves on these blueberry plants growing in the cool shade along a boardwalk near Illulisat icefjord in western Greenland are already turning red in early August!

16. Plants have adapted in to these short growing seasons in many ways.

This includes vivipary, where seeds germinate while still on the plant, and these little seedlings drop off to the ground.

Lots of plants have wind-dispersed seeds, and others have flowers that don’t need a pollinator to make a seed. The seed is a clone of the mother plant.

17. Unfortunately, climate change is happening and growing seasons are getting longer.

It’s unlikely that all of these amazing arctic plants will be able to adapt to these new conditions.

18. If you’re lucky enough to get to the arctic before the glaciers melt, how would you know what you’re looking at?

Lots of great plant identification manuals can show you where to find plants, and what they look like.

19. And, because there are so few species, getting a handle on them is easy.

20. There are also lots of lichen species. A lichen is a symbiosis between some fungi and photosynthetic bacteria. They are very well adapted to growing in harsh environments.

21. Finally, here are a couple of examples of how the Inuit use arctic plants.

Here’s a lighted kudlik, the traditional soapstone lamp that burns seal oil. The wick is made from arctic cotton grass, known in Inuktitut, as pualunnguat

22. Like in Ontario, berries are very popular, and blueberries, which grow tiny and sweet are everywhere!

23. That’s all from me on amazing arctic plants – if you’d like to learn more, please google this article.