Sad News over the Weekend:

Update September 30 2015: I was very sad to hear on Sunday, that my chief editor and the lead author on Ecology: A Canadian Context 2nd Edition, Professor Bill Freedman had lost his battle with cancer. It's just under a year since Bill told me about his diagnosis. I've thought of him often, but to my great regret, we didn't have a chance to talk again - I was teaching a lot and in April had a back injury that kept me out of the lab and field for the past 5 months.

Bill was ridiculously young - only 65. With his death, Science, Conservation and Ecology have all lost a very, very clever, kind, warm, inspirational man, who was the ultimate team builder and cheerleader for humanity and biodiversity. He was also a strong feminist and supporter of Women in STEM.

My Excellent Text Book Writing Adventure: In 2001-02, I taught a Bethune College first-year course called Where do Biological Facts Come From? (BC 1800 handout 2002). It challenged students to think about the sources of the information in their first year Biology text book. It was a lot of fun, and some of the students actually connected with the authors of research cited in their texts.

My Excellent Text Book Writing Adventure: In 2001-02, I taught a Bethune College first-year course called Where do Biological Facts Come From? (BC 1800 handout 2002). It challenged students to think about the sources of the information in their first year Biology text book. It was a lot of fun, and some of the students actually connected with the authors of research cited in their texts.

What we didn't specifically address were the questions:

- Who writes these commercial text books?

- Are the authors mainly professors who actively do research, as well as teaching, or others?

I recently saw my friend, Prof. Marie Josee Fortin (who should have her own Wikipedia page). I discovered, in passing, that she had never seen the 1st or 2nd edition of Bill Freedman et al.'s Ecology: A Canadian Context textbook, featuring her as a Canadian Ecologist. She was one of the only women in that edition (left).

I recently saw my friend, Prof. Marie Josee Fortin (who should have her own Wikipedia page). I discovered, in passing, that she had never seen the 1st or 2nd edition of Bill Freedman et al.'s Ecology: A Canadian Context textbook, featuring her as a Canadian Ecologist. She was one of the only women in that edition (left).

In 2005, my NSERC discovery grant, which I had held for 15 years wasn't renewed. The reason for this was my drop in publications (kids and all that). The fact that no one in York administration or NSERC ever let me know that there are automatic one-year extensions for the year in which one has a child, and that all I needed to do was apply, is a story for a different post, on ongoing barriers to women in STEM.

Why am I telling this story? Because, when I received the letter to say that my NSERC grant had been cut, one reviewer actually wrote, that a publication I had submitted as evidence of research activity, namely, a Cambridge University Press monograph that's still in print: "wasn't a scientific publication". So, if you suspected that scientists shouldn't publish books, you have no need to look any further for evidence of the reason why.

This all happened immediately prior to Prof. Gunhild Hoogensen and I receiving a $1.6 million International Polar Year grant in 2006, so, truth be told, I wasn't much bothered. In fact, I was relieved, because it allowed me to get off the NSERC hamster wheel and on to the interdisciplinary hamster wheel of publish or perish.

In addition to Myers and Bazely (2003) Ecology and Control of Introduced Plants, Cambridge University Press, which was considered to be a non-research publication by one of my erstwhile anonymous NSERC grant reviewers, two more books with which I was involved, came out in 2014. The first, an edited volume with Gunhild and two of our former graduate students, and the second, the 2nd edition of the aforementioned ecology text book. Hey, NSERC, look at me writing books and still doing ecology research that's published in STEM journals!

Researchers and Text Book Authors can be one and the same: The Ecology text by Freedman et al. is likely my first and last foray into the commercial side of science publishing. Why is this? It's not about the money. The world of text books is a lucrative market for some. Dominant texts in a subject, can, and do, make a ton of money for their authors. Additionally, being a top-text book author isn't mutually exclusive with being an active researcher. In ecology, the top text book authors, people like Charley Krebs and the Begon, Harper (dec.) and Townsend continuum were, and are, also, very active researchers.

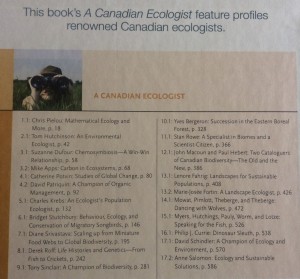

Reflecting back on my text book writing process, I'm very glad that I did it, because I learned A LOT! Plus, I was able to influence the information that some (and, I hope, many) Canadian undergraduate students will read: for example, there are many more female Canadian ecologists covered in the 2nd edition (left) than in the 1st edition. I had a been an external reviewer for the 1st edition and, along with others, had commented heavily on the absence of featured female Canadian ecologists. Bill listened and made this a priority for the 2nd edition. I gave input and got to write the entry for Prof. Diane Srivastava.

The text book writing experience was entirely different from that of writing a monograph with Cambridge University Press and an edited volume, with Earthscan (Routledge). The latter books are considered scholarly (though NOT science publications). I'd say that the difference between these more scholarly books and the text book, is that the former aren't really expected to be picked up by non-experts and/or practitioners in the field.

Text book writing was a steep learning curve that took me back to the intellectual pain levels of writing my MSc and DPhil. During the recent process, I interacted with a team of editors, illustrators, copyright people; a lot of delightful people in Canada and also India.

Text book writing was a steep learning curve that took me back to the intellectual pain levels of writing my MSc and DPhil. During the recent process, I interacted with a team of editors, illustrators, copyright people; a lot of delightful people in Canada and also India.

I joined the 2nd edition of an ecology text book that had a very specific vision. My task was to add the plant section to a Physiological Ecology chapter, which, in the first edition, only covered animals. The first 100 pages of text that I wrote were organized in a way that mirrored the animal side of the existing chapter. However, they were very nicely rejected, as not having a good flow. So, it was back to the drawing board, for a re-organization of the information and, new text. Ultimately, quite a bit of what I wrote was left on the editing room floor. But, I knew up front, that it would be like that.

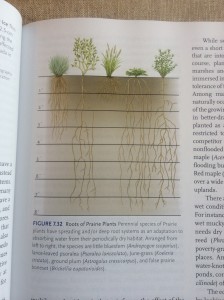

At the end of the day, I learned a lot about copyright and about the financial cost of including figures from research papers. For example, the information for Figure 7.32, at left, fell into the realm of common knowledge. I traced the source of this figure, which is seen in various manifestations in many text books, back to Shively and Weaver 1939 at the University of Nebraska! A very nice thing that I got to do, was to support the chief author (the very supportive and patient Bill Freedman, who should also have his own Wikipedia page), in producing a 2nd edition that directly addressed and remedied the lack of Canadian women ecologists in the 1st edition.

Interestingly, I've already received my first royalty cheque. I don't think it's going to make me rich, but, it's more than I earned at this stage from my other two scholarly books.

So, who should write science text books? I believe that it should be people like me: professors who both teach and do research. While this text book clearly isn't a research publication, it will be a first introduction for young ecologists to the field of Ecology during their university years. The problem is, that writing textbooks is an arduous, time-consuming process. It's one that junior faculty should definitely avoid, from a publish or perish perspective. Yet, I learned much from doing it that would have helped me in writing research papers. These are tough questions that those of us in Higher Education should debate, as we move into an era of shrinking funding and increased pressure on the university as a place that builds the larger public good.

Dawn Bazely