The reason I am late by a week with this post, is that I spent a ton of time last week:

1. With inspiring high school students and great colleagues (at right). For the 2nd year, I judged the Toronto Envirothon at the Ontario Science Centre.

1. With inspiring high school students and great colleagues (at right). For the 2nd year, I judged the Toronto Envirothon at the Ontario Science Centre.

2. With inspiring university students: I edited the publishable research of my undergraduate BIOL 4000 honours thesis students, Andre Oliveira (@Biol4095AndreO), Michelle Binczyk (@MichelleBiny) and Lucas Colantoni (@lucas_colantoni). They are getting a top-notch undergraduate supervisory experience similar to what students at Oxford and Cambridge universities receive. In the process, they are producing research that often matches or exceeds that coming from many master's programmes. Additionally, I was blown away on Monday night by the York-Sheridan Design programme student showcase, where Yan Hao (above, @ShawnHao1), who worked in my lab last year, presented his Seeker app concept.

2. With inspiring university students: I edited the publishable research of my undergraduate BIOL 4000 honours thesis students, Andre Oliveira (@Biol4095AndreO), Michelle Binczyk (@MichelleBiny) and Lucas Colantoni (@lucas_colantoni). They are getting a top-notch undergraduate supervisory experience similar to what students at Oxford and Cambridge universities receive. In the process, they are producing research that often matches or exceeds that coming from many master's programmes. Additionally, I was blown away on Monday night by the York-Sheridan Design programme student showcase, where Yan Hao (above, @ShawnHao1), who worked in my lab last year, presented his Seeker app concept.

3. With an inspiring environmental NGO: Carolinian Canada Coalition. I worked all last Saturday, doing my duty as a volunteer Board Member, at the Go Wild, Grow Wild show in London, Ontario (below right).

This means that I prioritized supporting these initiatives and students, rather than post a blog on time. I made a choice that had an opportunity cost, deciding that my greatest impact last week would arise from these people-oriented events and tasks (#WhatIsImpact? It's tough to measure). Everyone needs to understand the concept of Opportunity Cost: it's what you could have been doing during the time spent on a current task. I am now tired from all of these lengthy, public and supervisory activities, but also energized.

Most of the stuff I did this last week falls under Academic Citizenship, which the Times Higher Education magazine describes as the invisible glue that holds higher education together. Yesterday, I read a fabulous blog by Adam Micolich, on science career advice. It's mainly about how to be good academic citizen.

The 3rd part of my professor's job, beyond teaching and research, involves doing my duty on academic administrative work. To a large extent, this involves interacting with administrative staff, including deans, vice-presidents and the like. I'd like to say that working with the current incarnation of the York University administration leaves my feeling similarly energized and empowered, even when tired out with all of the paperwork. Sadly and annoyingly, this is not the case.

Last year, I bought an application called ATrackerPro to track my many fruitless hours spent interacting with York University's administration. I did not claim this expense, because trying to get our reimbursements has become incredibly cumbersome. There are more pressing uses for my time, so I just ate the financial cost (apparently, this makes me different from some members of the Canadian Senate).

The opportunity cost of dealing with the current York university administration, which in my opinion and extensive experience, seems to wantonly waste faculty and student time, has become sky high. It hasn't always been this way. One explanation is that these people are so completely disconnected from the front-line work of teaching and research, that they don't understand the impact of their behaviour. Kirk Englehardt (@kirdenglehardt) recently wrote a great blog asking "What is Impact?". The #WhatIsImpact link above, is his follow-up blog to his question.

The opportunity cost of dealing with the current York university administration, which in my opinion and extensive experience, seems to wantonly waste faculty and student time, has become sky high. It hasn't always been this way. One explanation is that these people are so completely disconnected from the front-line work of teaching and research, that they don't understand the impact of their behaviour. Kirk Englehardt (@kirdenglehardt) recently wrote a great blog asking "What is Impact?". The #WhatIsImpact link above, is his follow-up blog to his question.

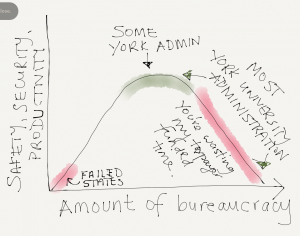

Let me be clear that I am a fan of bureaucracy. I like rules and following them. But, I also did my doctorate on applying optimality models to (sheep) behaviour. Consequently, I tend to think in an optimality kind of way, and this figure illustrates how I think about bureaucracy. After a month long strike, the York University admin leadership would do well to reflect on their contribution to my daily opportunity costs and do something to change their collective behaviours. In the interest of offering some constructive advice about how to keep oneself academically, grounded, here's my challenge to senior members of the York University administration:

1. Teach a 1st or 2nd year undergraduate course for the next 3 years and be so good at it that students (not members of the administration) nominate you for teaching awards after 3 years back in the classroom.

2. Go back to your research and within 3 years of doing this, get published in a top-tier journal (or pump out a book published by an elite press).

Pareto's Principle suggests that 20% of you will manage this.

Dawn R. Bazely