In April 2018, I spent a month as a visiting professor in the Biology Department of Monash University in Melbourne. The fabulous Professor Joslin Moore was my host, and I got to hang out with her welcoming and dynamic ecology research group. While there, I also visited colleagues and relatives in Brisbane and Sydney, where I did all the usual biodiversity and ecotourism things, like visiting the Blue Mountains west of Sydney.

During my too-brief first time in Australia, I was reminded of my 2004 visit to Capetown, South Africa. The flora and ecology surroundibg me in both places were completely alien, and astonishingly different from the northern hemisphere botany and biomes that I know so well. My "home" biomes are the temperate deciduous forests, grasslands, tundra and salt marshes of North America and Europe.

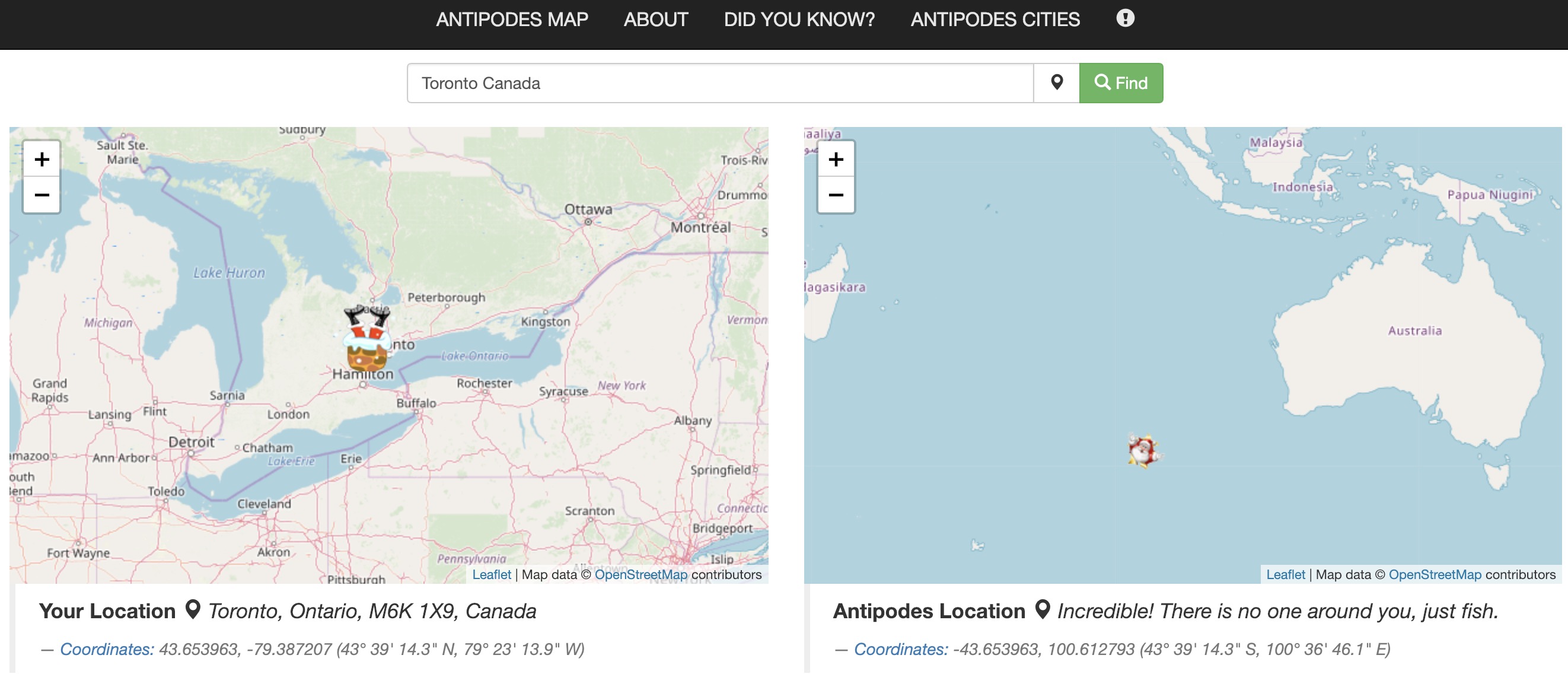

I remember getting off the plane in Capetown and sniffing the air. Its scent was completely unfamiliar. I had the same experience on arrival in Melbourne and Sydney airports. I also finally understood how REALLY far away Australia is from North America. The very cool Antipodes Map website lets you tunnel, virtually, to the other side of the world. When I tried the map, starting in Toronto, I ended up in the ocean pretty close to Australia (see above)!

I could imagine the early European botanists who visited Australia being completely mystified by the plants that they encountered. Naturally, they sought parallels and concordance with familiar flowers and trees that they knew from home. I discovered that they gave Australian plants some of the same common names, yet clearly these species have no taxonomic relationship to their British namesakes.

One Australian plant group entranced me more than any others: the Banksias, in the family, Proteaceae.

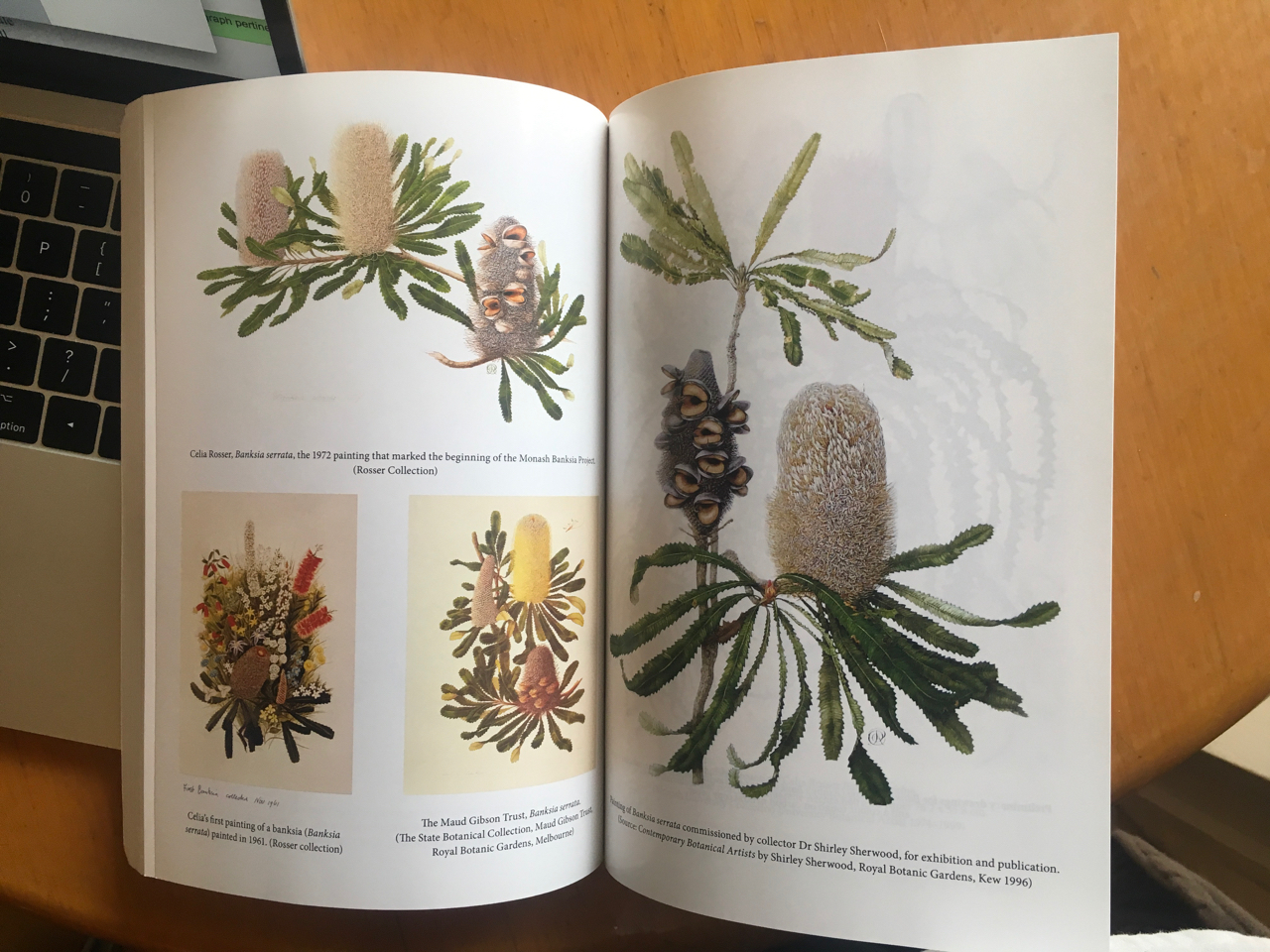

I loved the life-sized prints of different Banksia species in the hallway near my temporary biology office at Monash. When I visited the Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne, I learned about Celia Rosser, their incredible botanical artist. I also discovered that the drawings of the Banksia species were part of a decades-long project at Monash University.

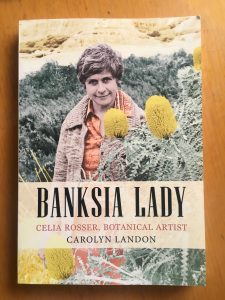

Carolyn Landon's 2015 biography, Banksia Lady: Celia Rosser, Botanical Artist is a fascinating read. The Acknowledgements open with "Celia Rosser's story has taken me on a journey through the history of Australian discovery, botany, botanic gardens, libraries, archives and botanical illustration." In fact, the book is about much more than this, including institutional and higher education politics, battles over the role, and value of science communication and public science, and who should pay for this public good.

Young scientists concerned with today's politics and policies around the funding of science, public science, and science communication, would do well to read this story of an artist who persevered for the sake of science. There have always been political battles over science and education, but knowing aspects of this particular history will serve today's early career researchers, keen to gain insight into institutional politics, well.